BICKERSHAW FESTIVAL

Bickershaw, a sleepy little Northern town, had certainly never seen anything like it before. Coronation St. had been invaded by the day glow kids and what fun they all had. Despite promises by the promoters of a flat, well drained site, too little sun and too much rain reduced the ground to one large mud pack – and it stayed that way for the entire festival.

On all sides one was treated to the sight of muddied stoned hippies negotiating their way across the site. Needless to say there were many casualties.

This was in fact, the worst aspect of an enjoyable festival. The Bickershaw Festival, financed by three Manchester business men, and run by Jeremy Beadle, local whizz kid, was the usual mixture of good and bad. The local farmer went to milk his cows and found they were all dry, some one had got there before him

On the credit side there were plenty of facilities for the freaks – large dormitory tents dotted around the site, some firewood and polythene, plus a range of entertainment aside from the music, which included the Electric Cinema tent, theatre groups, an aerial display with six bi-planes, fireworks plus assorted high divers, fire eaters, acrobats and high wire bikers. So on that level it was possible to have a fairly comfortable time despite the rain.

Whatever happened to Dion?

Biggest bummer of the weekend was the security force, yes, those deformed thugs who managed to turn Weeley into a scenario for a gangland movie were out in force and generally making their presence felt. If you're going to have a paying festival you need security but is it really necessary to hire a bunch of illiterate gangsters whose only answer to any question is "do you want a smack in the head mate?" One guy even admitted that he couldn't tell whether a pass was valid or not as he couldn't read... There were numerous incidents, especially around the stage, of people being beaten up and harassed, which is something you don't need.

The organisers were greedy, a fact made obvious when it came to concessions. There were at least two cases of concessionaires being overcharged by at least 100 pounds. The exclusive hamburger concession was sold to at least three people: one guy was forced to raise his prices from 20p to 30p when a gang of heavies from another hamburger consortium threatened him. In addition to that there were at least twenty food tents on the site, a trifle unnecessary for 30,000 people.

Despite many rumours the local police were cool. According to Release there were about 30 drug busts, a few drunk and disorderlys, and unknown charges against 18 Hells Angels who were busted on the way there. There were hundreds of uniformed police out to deal with traffic and any emergencies and probably half a dozen drug squad officers wandering around the site. The only good thing about the busts was that the police had set up an instant legal aid and analysis system, which meant that all those arrested were dealt with immediately and did not have to come back to court at a later date to have their case heard. The average fine was about 20 pounds although three people were remanded for psychiatric reports. The only large police operation came when 100 uniformed guys went through the site looking for a lost three year old child. No doubt they caused a few cases of acute paranoia but there were no busts. Unfortunately Release's relationship with the police was better than with the promoters, whose cheque for their fee for their services bounced. Add to that the fact that they had no electricity provided, and food vouchers for their staff of volunteers and doctors failed to materialize, and all this despite the fact that Release had offered some of the festival promoters the use of a bad trip tent to get their heads together. However, the White Panthers liberated a number of crates of beer, juice and other useful items to keep the wheels oiled. Thanks lads.

Aside from these hassles was the music which was generally of very high quality despite a somewhat ineffective PA. The stage, designed by Ian Knight of Roundhouse fame, cost 9000 pounds to build and was probably one of the most effective yet, reducing band changeover time to a minimum. On either side of the stage there were large platforms backed by screens so most people who wanted could get a fairly close look at the bands. On the screens there were light shows and close-ups of the bands in action, an advantage if you were sitting a fair way back. The local people flocked on the site to see the hippies at play and were by most accounts very friendly; the Frendz staff even had a drunken knees-up with a bunch of them during the last few numbers of The Dead's first set, and it was a toss up as to who was screaming for more louder when they'd finished playing. Power to the jam butty!

Bickershaw was not the bummer it might have been. Jeremy Beadle has announced that they lost 60,000 pounds. Underground press hacks wandered the crowd in a suitably damaged condition. Many were to be seen looking for earthworms in the ground – at least I presume that's what they were doing.

But the people got it on. Hippies have a remarkable talent for surviving in all weathers, under all conditions and still enjoying themselves, which is the only reason that things stayed together. Video freaks got good tape of the Dead and others – more of that in future issues.

The Music

Friday's musical entertainment was pretty tepid apart from our old mates Hawkwind (Dikmik gets the Frendz nomination for spaced oddity of the festival) while Nik "Thunder Rider" Turner ties with Dr John and Zoot Horn Rollo for the best dressed freak who blew a cosmic note or two. Otherwise the poor sods in the audience had to content themselves with anything from miserable folkies like Jonathon Kelly to the equally feeble Wishbone Ash. However, if you could stay awake during all this mediocrity, it was worth it all just for a glimpse of the immaculate Dr Jon Creaux and his nine piece band. Here is a real showman, dressed in white top hat and tails, his beard studded with silver pins, throwing Gris Gris glitter everywhere. He made Leon Russell look like Edmundo Ross. The Doctor took his band, complete with horn section, hotshite drummer and two little yummy gospel wailers – through the tightest changes imaginable, playing lead guitar on the stuff like 'Walk on Guilded Splinters' and unbelievable piano on the rest including 'Twilight Zone', 'Glowing' and a great selection of R&B killers like 'Let the Good Times Roll' and 'Iko Iko'. It was all good show biz voodoo, but don't think he isn't capable of the real thing.

Saturday saw a morning of jazz which Frendz' intrepid rock and roll reporter slept through. I awoke to hear Maynard Ferguson blowing his paunch out on 'MacArthur Park' and promptly fell asleep. An afternoon of folk failed to inspire me – Linda Lewis did her usual cutesy act, the Incredibles were a trifle too precious for my liking, whilst Donovan did a "Greatest Hits" act which was nice. He might also be very precious but at least he's professional about it. Rock appeared in the form of boogie beast Captain Beyond, a new American band who play the same old licks over and over and go nowhere fast. Tell ya, these guys are so hip they even do a 25 minute drum solo. Sam Apple Pie were a surprisingly good rock and roll band, while Cheech and Chong gave the kids some light comedy relief. Family played their usual set – a few hot licks and broken mike-stands, while the Kinks disappointed. Ray Davies – more effeminate and camp than ever (camp in the Noel Coward rather than the Alice Cooper sense) as well as being pissed as a newt – led what was essentially a mediocre live rock band through a boring set. Doing numbers like the 'Banana Boat Song' and 'Baby Face' didn't help matters much either and an encore of 'Hootchie Cootchie Man' was nothing short of farcical.

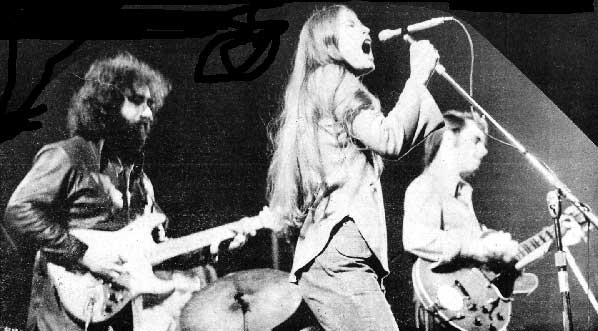

But never fear, The Flaming Groovies were on next laying out some cool assed jive. These boys are real gone – they sat around the stage before their performance drinking whisky, clicking their fingers, talkin' jive. When they hit the stage, the magical connection was lit. Young girls wept, policemen handed in their badges and joined the church, and some evil bikers staged a mini Altamont down the front of the stage while the Groovies bopped through 'Jumpin' Jack Flash', 'Nervous Breakdown', Lou Reed's 'Sweet Jane', 'Teenage Head', a couple of newies like 'Slow Death' and 'Shake The Joint' just like a juke box with balls.

After the gig, the bass player fell the full length of the steps to the stage, watched by the entire Frendz staff who were busy getting reacquainted with Captain Beefheart. Our fave rave got us all on the stage and played his usual total bizarro mind-fuck of a set. Superlatives defied us all so we promptly crashed out after the set, snarfing N.P. and dropping pork pies.

Sunday saw us up and raring to go. A fine set by the Brinsleys didn't stop the rain pouring down, but still sent out them good vibes we hippies are prone to talk about in elitist circles.

Country Joe was good, no more, no less and he left the stage for the New Riders of the Purple Sage who played a two hour set packed with goodies. Buddy Cage on pedal steel and Spencer Dryden on drums really stood out but this is a unit, now totally independent of the Grateful Dead's assistance. Nice harmonies, nice music, nice songs, what more could you ask for?

The Dead, that's what.

When Garcia and chums took the stage, the whole thing became a real festival. Everything was together and the Dead played for five hours, maybe more. Fireworks exploded, freaks danced and the band went through every change conceivable. A beautiful 'Dark Star' and a sizzling Pigpen work out on 'Good Lovin'' might be considered stand outs but really it was all music flowing like river. At 1am the Frendz collective slid off the planks, fell into the truck and hit the road south whistling 'Casey Jones' and snorting boiled sweets.

(by Nick Kent, from Frendz, June 1972)

http://www.ukrockfestivals.com/bick-frendz.html

* * *

A preshow interview with Jerry Garcia:

Q: Jerry Garcia - pouring with rain up here - what does the site look toward tonight?

Garcia: Well, muddy, of course, cold.

Q: You still going to play?

Garcia: Oh yeah, I think we're gonna play, yeah.

Q: Now, thousands of these people are streaming into tents and things, and a lot of people want to put restrictions on festivals in this country, as to the size and magnitude of mass festivals. Do you think festivals like this should have rules?

Garcia: Umm.... Well, that presupposes that I think that there should be festivals.

Q: This is the second festival you've played in this country, the first one being the Hollywood Festival two years ago.

Garcia: That's right.

Q: Now, that was quite a good festival.

Garcia: Compared to this one, yeah. (laughter) What you can do for a thing like rain or cold is like questionable, you know, what can you really do, not really much.

Q: And also the facilities for several thousand people out there, I mean the toilets are terrible, the size of the sea of mud, and also they've made complaints about the garbage out there.

Garcia: Of course, right, right. Well, that has to do with being able to -- the promoters should see that they have a responsibility to try to keep the site as reasonable as possible and so provide lots of opportunities for people to throw things away and clean up and that --

Q: Do you think they've failed abysmally?

Garcia: Well, I haven't been here enough to really determine. In my mind, most of the people I think are, you know, sort of accepting what's going on; I mean, it doesn't seem to me that anybody is really super uptight; but like I say, I'm not really 100 percent in touch with the whole thing, you know, so I can only give you my own fleeting impressions.

Q: Now, you're going onstage later on this evening, now you're apparently going to play for several hours, or you're planning to.

Garcia: We're hoping to, yeah

Q: Even despite the rain?

Garcia: Well, yeah.

Q: It still feels good?

Garcia: Yeah. I mean, we would not not play under any circumstances, because we've already agreed that we would play.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0vAqnq1vW0

* * *

Muther Grumble also did a short article on the Bickershaw Festival in their June 1972 issue, "The Great Western Rip Off":

The site, near Wigan, can only be described as a mud bath. OK so

the organisers couldn't control the rain, but what about the pond

in the middle of the site which they said would be fenced off and

never was? Still, mud and rain soon dries and washes off and I think

that's the way most other people thought about it.

Anyway, the music was good all weekend - and

so were Joe's lights, notably during Hawkwind's set on Friday.

There were good performances

from 'Captain Beefheart', 'Dr John', and 'Country Joe' who put life

back into the crowd with nice music and a long 'fuck Nixon' chant.

He was followed by a nice set from 'New Riders of Purple Sage', and

then along came 'The Grateful Dead' who played really excellent sounds

for 5½ hours that I can only describe as Far Out!

A good firework display was put on as the 'Dead' played. Other big

commercial attractions were the giant video screens each side of

the stage, circus acts and an aerial display no less. The screens

were certainly welcome as they meant that people could at least see

the stage without getting squashed at the front. It's a shame they

don't work during the day....

The circus acts, although good, were obviously an extravagant extra.

I would like to add that 'Time Out' did a good job with their information

points...

The organisers have since complained that they lost money due to

the large amount of people who got in for nothing. Shucks!

http://www.muthergrumble.co.uk/issue06/mg0628.htm

* * *

Melody Maker ran a long, detailed multi-page article on the Bickershaw Festival in their 5/13/72 issue, "The Day The Music Drowned." Here is an excerpt, the festival's conclusion with the Dead:

...As Sunday progressed, many people finally cracked, and made for home. But a core of some 15,000 took everything Mother Nature offered, and stayed for Grateful Dead, and got what they'd been waiting for - because the Dead blew a bigger storm...

...[During Country Joe's set] the Dead's equipment was set up. Despite his attempts, there was still a delay before the New Riders of the Purple Sage began playing. . . . While the stage area pulsated with attempts at organisation . . . the Jesus people took over the singing.

For a few moments the New Riders stood bemused and bewildered, uncertain how best to gain the initiative. Eventually they jerked into a few jagged guitar chords, and finally they gained enough ground to launch into operation without alienating the masses.

They began with attractive country flavoured numbers, clean instrumentals and Budd Cage effectively damping down the pedal steel and then breaking out with long metallic phrases. Unfortunately, there just wasn't enough variation in their music. The set became a fog of similar songs, distorted vocals and introspective jams. Although their opening numbers were refreshing, it was a relief when they got off the stage.

With America not being on, there was only one group left. It was obvious which one. The Grateful Dead's American road crew had virtually taken over the stage.

For a full half hour or more, the Dead played up to their name. They were dead. The festival seemed to be about to end on a marathon anti-climax. Changes began to happen around sunset.

The Grateful Dead slowly took a hold on themselves and their audience responded. They were playing a succession of short sharp numbers, very much the rock side of the group. Garcia picked out a whiplash lead and stared around the stage with owlish blankness.

Dusk approached and the light show behind the group flickered with subtle distortions of a fairground. It switched onto scenes of a steam train for "Casey Jones," and the music was really getting strong.

Just time for a quick half time and the Dead were back into the music. They were hardly recognisable as the same group that opened the show. Somehow their longer numbers like "Dark Star" and "Turn On Your Love Light" gave the impression that they were playing in competition with each other, but listen carefully to each instrument in turn.

The deep rumblings of Phil Lesh's bass chords and Bill Kreutzmann's drumming, the cutting guitar rhythms of Bob Weir, and most dramatically of all, Garcia's superb lead. The weird little phrases he played, with their bell tone and uncertain symmetry. The vital flames of feedback, beautifully controlled.

The purple spotlights focused on Garcia, "Dark Star" rebounded from atmospherics into its culminating rhythm, making the recording on the "Live Dead" album sound feeble in comparison.

Incredibly, at one point the security web around the Dead folded. A figure rushed across the stage, evading roadies. He threw his arms around Kreutzmann, forcing the drummer to stop playing. In his few seconds of struggle he apparently got across to Kreutzmann that he meant to die that night. Kreutzmann nodded and smiled sympathetically and returned to his stool. The frantic saboteur disappeared behind security.

Around midnight the Dead had been playing for about four hours, give or take one or two breaks. Rock returned as they began the final hour. A female friend came on occasionally to reinforce the vocals, and Pig Pen crept forward from his organ to belt out a few songs.

Eventually they came to "Not Fade Away" and Weir all but threw his voice away on it. An encore, and one final fling with "Johnny B. Goode."

It had been a sensational set, a worthy antidote to a weekend of mud.

http://www.gdao.org/items/show/829502

The Grateful Dead Archive Online has a scan of the full article: "Melody Maker (May 13, 1972): "The Day the Music Drowned", report on the

Bickershaw Festival by Roy Hollingworth, Andrew Means, Chris Welch."

* * *

This site has a number of links about the Bickershaw festival:

http://www.ukrockfestivals.com/bickershaw-menu.html

From the Grateful Dead section in the festival programme:

"You are part of the Grateful Dead and so is that guy next to you straining to get a look at your programme because he couldn't afford to buy one. Share it because you need each other as much as the Dead need each other and need your participation. "That's the ideal situation, everybody should be in the band." . . .

They grew in the days of legal and pure acid when the west coast was rubbing out signs and dividing lines and walking on the high waters of altruism and love. They played the Trips Festival, the Acid Tests and the Golden Gate Park Be-In and became actively involved in most of the things that were going down, taking them up and away. In 1968 they helped run the Carousel with the Airplane and some friends until the pressures of fuzz and finance forced a close down. Later Bill Graham moved in and renamed it the Fillmore West.

The Dead have been through busts, debts, and beatific bummers and have come out trucking when others have slipped back into old habits, been co-opted or just plain lost faith. Intangible and mysterious lines consorted to once again limit the boundaries, to divert that free consciousness back into seats with numbers watched over by a hierarchy of men with greedy wallets and uniforms who never really felt what was happening.

What's that sound? "Paranoia strikes deep," sung the Buffalo Springfield, and bombs, bad vibes and smoke screens have filled the air, but the Dead, sometimes distant, sometimes near, are still there with a good trip flying from their speakers, showing that the typical daydream can be its own creator and can channel its energy in positive directions.

Setting up the evening before their two night stint at London's Wembley Pool, someone called up to the stage, "Jerry, would you be happier if this barrier was nearer the stage?" To which that famed string picker replied, "We don't need no barriers man, nobody's going to attack us."

At the sound checks they eased through "Hully Gully," "You Win Again," and foolishly I thought that I was getting a sneak preview of the following night's concert. No way, the three and a half hour set on Friday took you through so many delightful changes that you had no idea where it would come from next. My head dropped off altogether when they slipped Marty Robbins' El Paso somewhere into The Other One. Wait til they do Not Fade Away, someone confided to a friend on Saturday night, as the Dead inched their way in little rushes through the disparate house lights and the formality of a slightly straitjacketed environment. Well that friend could still be waiting cos they never faded away but took you to see and hear other sights beyond the Dark Star... They often work within frameworks and call upon references but the number of directions they can take are infinite..."

Audience members generally remember how cold and wet they were, but there are a few memories of the Dead playing:

"I saw the Dead the first night at Wembley and don’t remember thinking then I’d be seeing them again so soon afterwards. Maybe, like the Lyceum gigs, it was announced whilst the tour was in progress. The papers were full of the Dead playing for up to nine hours, doing a run through their entire back catalogue, and the organisers confirmed they’d leave it open-ended to let the Dead play as long as they wanted...

I was disappointed when we reached the festival site. Probably the rain didn’t help but the whole atmosphere was bad – it felt like (and probably was) an industrial wasteland. From somewhere we commandeered a huge plastic sheet which, when it rained, we could sit on and pull up, over, and around ourselves, leaving a small hole at the front to look through... Apart from when the Dead were on, it just seemed to rain most of the time...

And then the Dead. At least the rain had stopped, and I think for once we stood up to watch. The whole festival area by now looked like a disaster area, with silhouettes moving through the mud against a backdrop of flickering fires. It was getting cold once the sun went down and, even from a distance, you could see the vapours being spewed out by the heater cannon on stage...

It was a far more mellow show than at Wembley and they took their time, easing into it gently. I was astonished and delighted to get both Dark Star and The Other One in the same show. Am I imagining it or were the words of Casey Jones flashed up on a screen with a bouncing ball tracking them?"

"A large yellow backcloth with a giant Stealie in the middle was

unfurled and billowed in the wind... I remember the band playing Dark

Star as the sun sank into the murky haze..."

"By this time most of the fences were down, the security was non existent and the villagers were in the festival grounds watching the good old Grateful Dead and seemingly liking a lot of it too. The first set finished with a rollicking Casey Jones, and the assembled multitude erupted in a spasm of chorus singing and dancing, villagers and all. The weak evening sun highlighted the whole weird mix. Frizzy haired freaks in the crowd playing soaking wet, tuneless hand drums next to flat capped miners, women in the traditional northern housewife's headgear of curlers and headscarves and their kids in prams all singing and leaping and becoming one in a flat out good old bacchanalian romp that would have done the ancient Greeks proud.

There was the inevitable break and then the Dead came back and launched into the stellar stuff, first a warm up with a few rockers like Jack Straw and Greatest Story and then into the REAL pudding - DARK STAR, followed by The Other One - both seriously out there versions and as the fireworks and the video screens got worked up nicely in the gloom, it finally cleared enough so the entire second set was free of rain."

"There were fireworks set off during Dark Star and everyone on the aud tape can be heard going "whooooo," a truly magic moment... I have the vision of the fireworks going off above the stage, for once the sky was clear and crisp (although it was still cold) and the band onstage were framed beautifully by the exploding starshells."

* * *

From Nick Kent's 2010 autobiography, Apathy for the Devil:

"...Another 'magic band' from America's West Coast who'd adopted LSD as a means to break down existing musical barriers and create a more wide-open sonic sensibility were San Francisco's Grateful Dead. Ever since 1967 they'd been fondly recognised as psychedelic-rock pioneers and all-purpose community-minded righteous hippie dudes by John Peel's lank-haired listeners throughout the British Isles, but they'd only ever managed to play one concert in England to date, at a festival in Staffordshire in the early summer of 1970. In early '72, though, the group and their record company Warner Bros. bankrolled an extended gig-playing trek through Europe that included a short tour of England. In late March, they and their extremely large 'extended family' moved into a swank Kensington hotel in anticipation of the shows and duly became my third interviewees.

In stark contrast to their reputation as championship-level LSD-gobblers, they seemed a pretty down-to-earth bunch when confronted one-on-one. They dressed like rodeo cowboys and talked like mature overseas students checking out foreign culture. The drugs had yet to bend their brains into some inexplicable agenda like Beefheart's bunch. Their music may have been further fuelled by a healthy desire to embrace utter weirdness, but none of them was weird per se. Jerry Garcia in particular was totally exasperated by their image and reputation and the way it constantly impinged on his privacy. Every acid casualty in Christendom wanted to corral him into some 'deeply meaningful' conversation and he'd simply had enough of indulging all these damaged people. Hippies the world over looked up to him as though he were some deity or oracle, but Garcia was really just an intelligent, well-read druggie with a deeply cynical streak who felt increasingly ill at ease with the role he'd been straitjacketed into by late-sixties bohemian culture. In time it would get so intolerable that he would withdraw from society in general by compulsively smoking high-grade Persian heroin. This in turn would prove fatal: after twenty years of addiction, the drug would end up hastening his death in 1995.

At the same time, he was one of the most singularly gifted musicians of the latter half of the twentieth century. The Grateful Dead were an odd bunch in that they were always being called a rock band but they couldn't play straight-ahead rock 'n' roll to save their lives. They'd started out instead as a jug band before branching out into folk and electric blues and playing long jazz-influenced jams whenever the mood struck. By the end of the sixties they'd even morphed into a credible country-and-western outfit. By 1972 they meandered between these various musical genres, performing sets that rarely ran for less than three hours in length; there were - inevitably - valleys and peaks. You'd sit there for what seemed like an eternity watching them noodle away on stage silently praying that they'd actually finish the song and put it out of its misery. But then - all of a sudden - the group would take off into the psychedelic stratosphere and Garcia would step forward to the lip of the stage and begin navigating his way to that enchanted region where the sagebrush meets the stars. Cosmic American music: Gram Parsons coined the phrase but it was the Grateful Dead who best embodied the concept even though - after 1972 - they began slipping into a long befuddling decline...

The Dead turned up to play at a three-day festival held in the Northern town of Bickershaw during the first weekend in May '72. The event's shady promoters had envisaged it as a grand unveiling of the whole West Coast live rock experience to the John Peel demographic, but it soon degenerated into a sort of mud-caked psychedelic concentration camp filled with miserable-looking young people on dodgy hallucinogenics being lashed by torrential wind and rain and being sold inedible food. The Dead performed splendidly [. . . .] but there was no getting around the fact that the whole ugly debacle was destined to be acid rock's last hurrah here in the British Isles. A relentless downpouring of bad weather, bad facilities, bad drugs and (mostly) bad music; it had worked like a charm three years ago at Woodstock but it wasn't working anymore.

Mind you, I had a great time. A bunch of Frendz collaborators had hired a large van we could all sleep in and had succeeded in getting VIP passes, so we were always close to the action and safe from the inclement storms raging over the bedraggled spectators..."